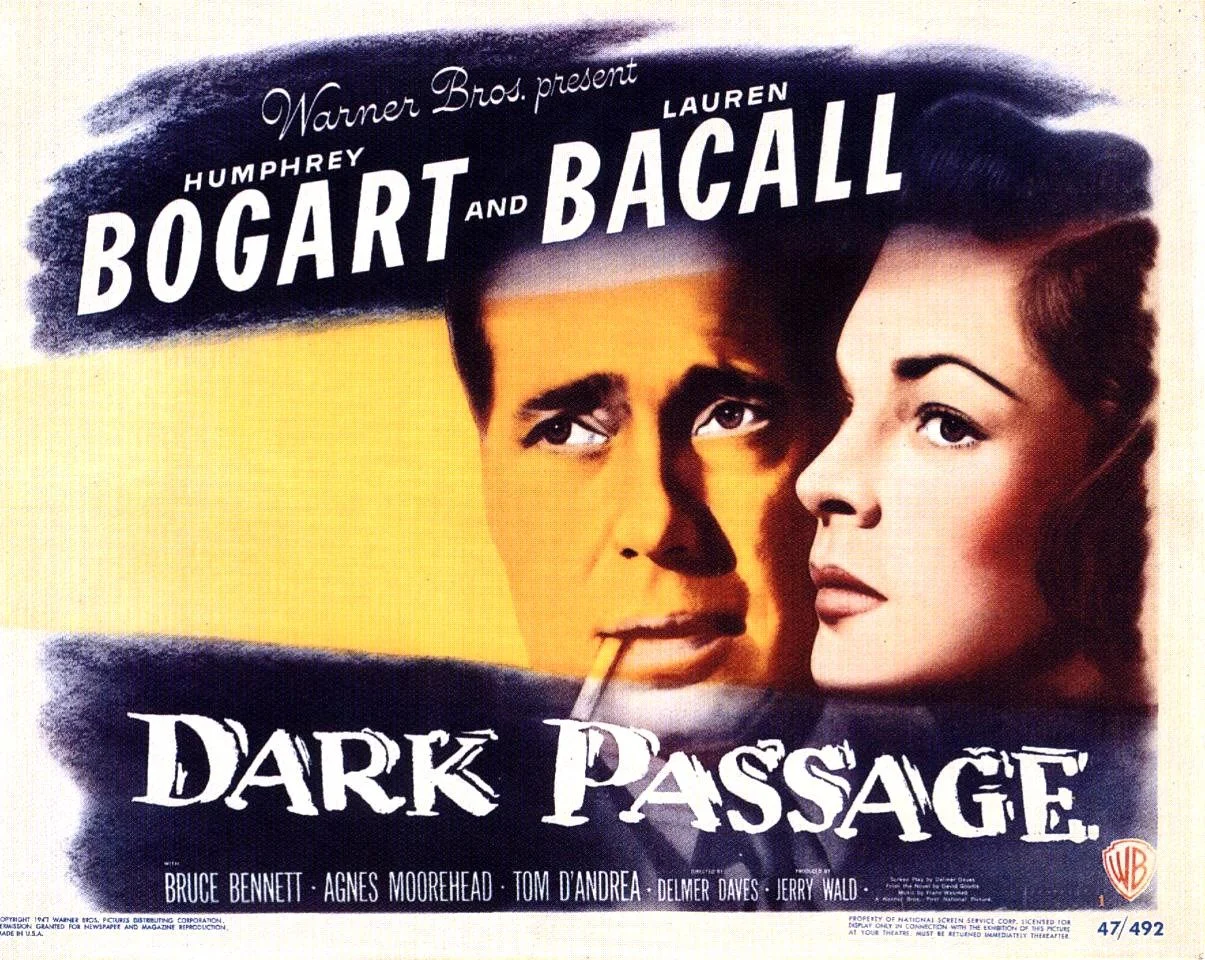

The third teaming of Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall turned out to be their most un-Hollywood movie together, as well as an endlessly fascinating experiment in cinema that was attempted a year earlier in Robert Montgomery's directorial debut 'Lady In The Lake', but was mastered in 1947 with this, namely to use the first-person perspective to tell the story.

Vincent Parry (Humphrey Bogart) has escaped from San Quentin, having been convicted of murdering his wife. On the run, he assaults an inquisitive driver (Clifton Young) who's stopped to give him a lift, and then finds himself rescued, out of the blue, by Irene Jansen (Lauren Bacall) who seems to know everything about him.

Utilising her aid, Parry manages to get to San Francisco, where he begins the process of piecing together the events leading up to his wife's death, but the killer is still out there, and is determined not to be caught.

Whereas Montgomery's movie from the year before hadn't fully exploited the first-person system to its full potential, 'Dark Passage' makes dazzling use of its technique, rightly concentrating less on the mystery itself, and focusing on generating maximum suspense for the viewer. Viewing the entire first hour through Parry's eyes, we are complicit in his fear and paranoia, as simple acts such as riding an elevator and making it from the car to a door become knuckle-gnawing exercises in tension.

We meet the supporting characters as Parry does, with a fresh pair of eyes, and therefore find ourselves cautious about misplacing our trust, alternating between delight and dismay as they prove or confound our expectations of them.

The use of a subjective viewpoint could almost be seen as gimmicky, but there is a genuine reason for not seeing Bogart's face in the first hour. It's simply that he's a different man in this section, glimpsed from time to time on the front of newspapers and on police reports. The face is almost Bogart, but not quite. The voice is unmistakeably his, but halfway through, director Delmer Daves pulls off another masterstroke.

After having surgery to alter his looks (to that of Bogart), Parry is unable to speak. For a period of the movie, we have the face, but we're now without the voice that has carried us thus far. Again, this isn't forced into the film to tick a box. It's a well thought out plot progression that serves the narrative.

The movie was filmed on location in San Francisco, and as such, adds to the suspense. Taking place on the streets at night builds on the tension as Parry makes his way around the city. There's a superb sequence that takes place around the halfway mark in which Parry must cross the entire city unnoticed, unable to speak, and swathed in bandages. No mean feat.

'Dark Passage' is often overlooked as a lesser effort when held up alongside the other Bogart Bacall pairings of 'To Have And Have Not', 'The Big Sleep', and 'Key Largo', but for my money it's the better of the four. It doesn't have the stilted stagey-ness of 'Key Largo', the head-scrambling plot of 'The Big Sleep', or the sultry-for-sultry's-sake-Hemingway-pretentiousness of 'To Have And Have Not'. Not that those films aren't sublime in their own right. They're simply not as inventive, as well-told, or as purely rebellious as 'Dark Passage'.

It's the most Hitchcockian film that Hitchcock never directed. Be the person that recommends this film to your friends, and spend the rest of your life revelling in the praise that they heap upon you as a result.

I won't tell.